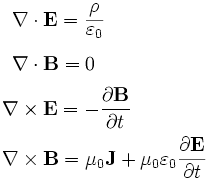

MAXWELL’S EQUATIONS

A set of four key equations which collectively organize and describe electromagnetism. The four

individual laws which these equations sum up were actually discovered earlier by other scientists,

but in 1861-62 James Clerk Maxwell brought these laws together in mathematical form in a way which

fully established the unity of electricity and magnetism in a clearer and more profound theoretical

way. Maxwell’s Equations have been formulated in various ways, but the modern method is to

formulate them in terms of partial differential equations in vector calculus, as shown in the

graphic at the right. These four equations represent in turn:

A set of four key equations which collectively organize and describe electromagnetism. The four

individual laws which these equations sum up were actually discovered earlier by other scientists,

but in 1861-62 James Clerk Maxwell brought these laws together in mathematical form in a way which

fully established the unity of electricity and magnetism in a clearer and more profound theoretical

way. Maxwell’s Equations have been formulated in various ways, but the modern method is to

formulate them in terms of partial differential equations in vector calculus, as shown in the

graphic at the right. These four equations represent in turn:

1. Gauss’s Law of Electricity: The electric

flux leaving a volume is proportional to the charge inside.

2. Gauss’s Law of Magnetism: No magnetic

monopoles exist; the total magnetic flux through a closed surface is zero.

3. Faraday’s Law of Induction: The voltage

induced in a closed loop is proportional to the rate of change of the magnetic flux that the loop

encloses.

4. Ampère’s Circuital Law with Maxwell’s

extension: The magnetic field induced around a closed loop is proportional to the electric current

plus displacement current (rate of change of the electric field) that the loop encloses.

A more thorough (and much more technical) discussion

of Maxwell’s Equations is available in the Wikipedia at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maxwell%27s_equations

“Although Maxwell’s equations are relatively simple, they daringly reorganize

our perception of nature, unifying electricity and magnetism and linking geometry, topology

and physics. They are essential to understanding the surrounding world. And as the first field

equations, they not only showed scientists a new way of approaching physics but also took them

on the first step towards a unification of the fundamental forces of nature.” —Robert P.

Crease, “The Greatest Equations Ever”, Physics World, Oct. 2004, online at:

http://physicsweb.org/articles/world/17/10/2/1

“The equations of electricity and magnetism that are today known as Maxwell’s

equations are not the equations originally written down by Maxwell; they are equations that

physicists settled on after decades of subsequent work by other physicists, notably the English

scientist Oliver Heaviside. They are understood today to be an approximation that is valid in

a limited context (that of weak, slowly varying electric and magnetic fields), but in this form

and in this limited context, they have survived for a century and may be expected to survive

indefinitely.” —Steven Weinberg, Nobel Prize winning physicist, “Sokal’s Hoax”, New York

Review of Books, Vol. XLIII, No. 13, pp. 11-15, Aug. 8, 1996.

“MAY FIFTEEN INCIDENT” [Japan, 1932]

“In October 1931, Japan’s reactionary military figures and Right-wing

militarists masterminded a coup with the aim of reorganizing the government. They intended

to install General Sadao Araki as Prime Minister to head a dictatorial military regime,

but their plan fell flat. In spite of that, pressure from the army which called for speeding

up militarization became all the more intense. Towards the end of the year, Tsuyoshi Inukai,

boss of the ‘Constitutional Political Friend’s Party’ (Seiyukai), came into power,

and Sadao Araki was appointed Minister of War. In 1932, people of all strata in Japan were

getting increasingly discontented with the government’s reactionary home and foreign

policies. Workers and peasants rose in struggle wave upon wave. Confronted with this

situation, the panic-stricken reactionary ruling circles tried to strengthen their fascist

rule.

“On May 15, 1932, the Right-wing

fascist group ‘Blood Pledge Society’ (Ketsumeidan), with the support of other

reactionary organizations, sparked off terrorist activities with another incident. A group

of young army and navy officers mustered by them broke into the residence of Prime Minister

Tsuyoshi Inukai and shot him. They also attacked the Metropolitan Police Agency. The

incident was designed to force the government to proclaim martial law so that a military

cabinet may be formed and a militarist system instituted. After the death of Inukai, Admiral

Makoto Saito, former Governor of Korea, formed a cabinet, again with Sadao Araki holding

the portfolio of War Minister. While quickening the tempo of militarization, the Saito

cabinet made big efforts to crack down on the people. Communists and progressives were

arrested and persecuted on a mass scale. On October 30, 1932 alone, 1,400 were arrested.

The Japanese people so came under a reign of fascist terror worse than ever.” —For Your

Reference note, Peking Review,

#50, Dec. 11, 1970, p. 14.

MAY FOURTH MOVEMENT

An important radical nationalist movement of Chinese students and intellectuals which grew

out of demonstrations by students at Tiananmen Square in Beijing on May 4, 1919. This

demonstration condemned both the unfair terms of the Versailles Treaty ending World War I

which granted significant territorial concessions from China to Japan, and also the weak

warlord government in control of Beijing which went along with this imperialist deal.

“‘May 4’ refers to May 4, 1919, when the anti-imperialist and anti-feudal

revolutionary movement broke out. In the first half of that year, Britain, France, the

United States, Japan, Italy and other imperialist countries that had emerged victorious

from World War I held a conference in Paris to divide the booty. A decision was adopted

which stipulated that Japan would take over all the privileges previously held by Germany

in China’s Shantung Province. On May 4 that year, the students in Peking took the lead

and held rallies and demonstrations to protest against the decision. When the government

of the Northern Warlords resorted to suppression, the Peking students suspended classes

in protest. Students in other parts of the country quickly rose to express their

solidarity. The Northern Warlord government made mass arrests in Peking, which aroused

still greater indignation among the people of the whole nation. The patriotic movement

so far participated [in] mainly by the intellectuals rapidly developed into a nationwide

movement participated [in] by the proletariat, petty bourgeoisie and bourgeoisie. As the

patriotic movement surged ahead, the new cultural movement against feudalism and for

science and democracy unfolded prior to the May 4th Movement developed into a mammoth

revolutionary cultural movement with the propagation of Marxism-Leninism as its main

current.

“After the founding of the People’s

Republic of China in 1949, May 4 was officially proclaimed China’s Youth Day.” —Footnote

in Peking Review, vol. 19, #22, p. 12, May 28, 1976.

MAY 16th ULTRA-LEFT GROUP

More formally known as the “May 16 Counterrevolutionary Clique”, the term adopted in August

1967 by the central leadership during the Great Proletarian Cultural

Revolution (GPCR) in China in condemning this group or trend. Originally this referred

only to a small group of college students in Beijing who called themselves the “Capital May

16 Red Guard Regiment”, named after the May 16 Circular of 1966 which was the formal beginning

of the GPCR (see entry above). This group secretly distributed leaflets and posted

big character posters condemning Premier

Zhou Enlai, calling him a “black back-stage

supporter of the February Adverse Current” and

a “shameful traitor of Mao Zedong Thought”, and said he had betrayed the spirit of the May

16 Circular. They proclaimed: “Thoroughly wreck the bourgeois headquarters! Hold Zhou Enlai

to account”.

Mao and the Central Cultural Revolution Small

Group directing the GPCR viewed this attack on Zhou as sectarian and disruptive of the unity

of the forces leading the Cultural Revolution. Consequently, a campaign was launched against

the Capital May 16 Red Guard Regiment and it was suppressed. The campaign then broadened and

went nationwide against similar ultra-left or sectarian trends, which were collectively

referred to as the “May 16th Ultra-Left Group”, or—in abbreviated form—as “Five-One-Six”.

Thus, ironically, “5-1-6” came from that point on to refer not to supporters of the

May 16 Circular, but rather to ultra-left or sectarian opponents of it.

In August 1967, when Mao was reading

Yao Wenyuan’s article “On Two Books by Tao Zhu”, he cited

the “May 16” group as an example of the counterrevolutionaries who, in Yao’s words, “shout

slogans that are extreme left in form but extreme right in essence, whip up the ill wind of

‘suspecting all,’ and bombard the proletarian headquarters.” Mao himself wrote: “The

organizers and manipulators of the so-called ‘May 16’ are just such a conspiratorial

counterrevolutionary clique and must be thoroughly exposed.”

Although the Chinese press referred to the

“May 16 Counterrevolutionary Clique” as a massive “conspiracy”, it is very doubtful that

there ever was any actual widespread (let alone nationwide) conspiracy. However, this does

not mean that there was not a genuine ultra-leftist sectarian trend within many Red

Guard organizations and elsewhere that was causing serious trouble and needed to be dealt

with. (This is sort of an inevitable result of relying on basically unguided and inexperienced

youth to become the leading force in a revolutionary movement, even for a limited period.)

In particular, this ultra-left trend created

considerable problems within China’s Foreign Ministry, and for China’s relations with other

countries. There were not only protests outside of many foreign embassies in Beijing, some

of those embassies were mildly damaged in attacks, with broken windows and their walls

covered with posters and graffiti. The Soviet and Indonesian embassies were partially burned.

In London there was actually a pitched battle between Chinese embassy personnel and London

police on August 29, 1967. Ultra-leftists within the Foreign Ministry took de facto control

of it, and provoked incidents and quarrels with over 30 countries, including not only the

USSR and old-line imperialist countries like Britain, but even “Third World” countries. In

June 1967 two Chinese-speaking diplomats of the Indian embassy were beaten by Red Guards at

the Beijing airport as they tried to leave the country after being expelled. Some Red Guards

even denounced North Korea’s Kim Il Sung as a “fat revisionist”; and though he may in fact

have actually been such a thing, this sort of “foreign policy” made things very difficult

for China economically and politically and drove it into extreme isolation. And, unfortunately,

this sort of infantile behavior eventually promoted a more rightist foreign policy than would

otherwise have been likely to develop. (This is a big general problem with ultra-leftism;

because of its absurd excesses which must be suppressed, the situation often tends to swing

too far in the other direction and even into revisionism.)

Chen Boda was

originally put in charge of dealing with the “May 16th Ultra-Left Group” but as the anti-“5-1-6”

campaign spread and became more generalized, he was accused of being a secret supporter of

those ultra-left ideas himself, and especially of making accusations against Zhou Enlai. Chen

then became a target of the campaign as well. However, he recovered from that criticism, as

did many others briefly targetted in the anti-“May 16” campaign. (It was Chen’s later close

association with Lin Biao which led to his complete downfall in

1970.) It is said that millions of others were accused of ultra-leftism too, and while this

was often overlooked later, over the long run this probably ended up considerably weakening

the left in China, and helping the capitalist roaders

overthrow the left after Mao’s death. This is another example of how ultra-leftism can play

into the hands of the rightists.

It seems like almost everyone else besides

Mao was also attacked at one time or another by various elements within this ultra-leftist

trend, even some of the (so-called) “Gang of Four” themselves! “The ‘bombardment’ against

Zhang Chunqiao in February, 1968, came not only from the

Right, but also from the ultra-Left, a fairly strong group in Shanghai which had broken with

Zhang the year before because they considered him too moderate. This explains why the

librarian [an individual recounting his mistreatment by the ‘Gang of Four’ after their

downfall]—doubtless no ultra-leftist himself—could have come to be associated with the May

Sixteenth group. The quarrels and hates between various currents of the Left in Shanghai were

without doubt exploited by the new leaders during the campaign against the Four, and were some

of the reasons that made impossible a coordinated resistance against the Right’s coup.”

[Edoarda Masi, China Winter (1978), p. 308.]

It is an actual fact that, as noted in

Peking Review during the GPCR [Jan. 6, 1967, p. 8] everyone in present-day

bourgeois society is really a target of the

revolution, including the members and leaders of the revolutionary party and, yes,

including even each one of us ourselves! However, it is also a fact that everyone is

not the enemy of the revolution, nor is everyone to be attacked and criticized at

every point in the revolution. Every revolution, to be successful, must unite the vast

majority against the small number of genuine die-hard enemies at that point. Later the

struggle may focus on different issues, and there will be different people to criticize and

different people who resist the changes which are necessary in society and in themselves. But

to make everyone the enemy is the mark of utter foolishness and infantilism, and will

inevitably lead to the complete failure of the revolution. A firm grasp of dialectics is

definitely called for here!

“[Mao] told me ... those officials who had opposed my return to China

in 1967 and 1968 had belonged to an ultraleft group which had seized the foreign

ministry for a time, but they were all cleared out long ago.” —Edgar Snow, from a

report of a conversation he had with Mao in December 1970, Life magazine,

April 30, 1971. Online at:

https://www.bannedthought.net/Journalists/Snow-Edgar/EdgarSnow-Life-1971-April30.pdf

MAZUMDAR, Charu (1918-72)

[His family name is also often transliterated from Bengali as “Majumdar”.]

[His family name is also often transliterated from Bengali as “Majumdar”.]

A great revolutionary in India who was the leader of the famous armed Naxalbari uprising of

peasants in 1967, and one of the main founders of the modern Maoist movement in India. He led

in the formation of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) in 1969 as a split-off

from the revisionist Communist Party of India (Marxist). In 1972

Mazumdar was captured and tortured to death by police, and the CPI(M-L) fractured into many

pieces. However, the current powerful and rapidly growing Maoist-led revolutionary movement

in India has come together from some of the segments of that old party together with other

Maoist forces who had remained outside of the original CPI(M-L).

Charu Mazumdar was born into a progressive

landlord family in Siliguri, West Bengal, in 1918. Even as a teenager Mazumdar rebelled

against social inequalities, and joined up with the All Bengal Students Association, which

was a group of petty-bourgeois nationalist revolutionaries affiliated with the Anusilan group.

By the age of 20 he had dropped out of college and joined the Congress Party, and became an

an organizer among bidi workers. He shifted further left

and joined the Communist Party of India, and worked in the Kisan Sabha, its peasant

organization, with the poor and oppressed peasants in Jalpaiguri and Darjeeling. An arrest

warrant was issued for him, and he had to go underground for the first time.

The CPI was banned at the beginning of

World War II, but Mazumdar continued his peasant organizing work and was elected to the

Jalpaiguri district committee of the CPI in 1942. In 1943, mostly because of the British

imperialist looting of so much of India’s grain and their indifference to the welfare of

the Indian people, a major famine broke out in West Bengal. [See:

Famines—Imperialist Caused] Mazumdar organized a

fairly successful ‘seizure of crops’ campaign by the peasants in Jalpaiguri during this

famine.

In 1946 Mazumdar joined and help lead

the Tebhaga Movement of peasants trying to keep

more of their harvests from the grasping hands of the landlords. This movement helped

shape his conception of revolutionary struggle, and also helped prepare the peasant

masses for future revolutionary struggle. Later Mazumdar worked among tea garden workers

in Darjeeling. In 1948 the CPI was banned by the government, and Mazumdar was imprisoned

for three years. In January 1954 he married fellow CPI member Lila Mazumdar Sengupta.

A growing ideological struggle within

the CPI developed after its Palghat Congress in 1956, and Mazumdar quickly gravitated

toward the revolutionary left wing. In 1962 he was again imprisoned for opposing the Nehru

government’s war against revolutionary China. In 1964 the CPI split, reflecting within

India the Sino-Soviet Split, and Mazumdar joined the breakaway CPI (Marxist). But he

disagreed with the CPI (Marxist)’s electoral policy and decision to postpone armed

struggle until some indefinite point in the far future.

During the mid-1960s Mazumdar organized a

left faction within the CPI (Marxist) in northern West Bengal. He was in poor health in

1964-65 but devoted this time, even while in jail, to studying and writing about the path

of the Indian revolution on the basis of Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tse-tung Thought. This led

to his very influential writings and speeches in the 1965-67 period, which were later

called the ‘Historic Eight Documents’.

In 1967 the CPI (Marxist) [or “CPM” as

it is generally known] betrayed the revolutionary movement by joining with the bourgeois

party, the Bangla Congress, in a coalition government in West Bengal. But on May 25 of

that same year Mazumdar showed there was another road possible by leading the peasants

in the vicinity of the village of Naxalbari in the Darjeeling district of West Bengal in

a historic uprising. The rebels annihilated a notorious police inspector, and took the

first step in launching the New Democratic revolution in India. The state government’s

Home Ministry, headed by the CPM leader Jyoti Basu, brutally suppressed this uprising,

and even murdered 11 women and 2 children in the process. But the ideology of “Naxalism”

spread rapidly and inspired revolutionaries around India and South Asia.

Many revolutionaries within the CPM, from

7 different Indian states, then set up what was originally called the All India

Coordination Committee of Revolutionaries (AICCR), on Nov. 12-13, 1967. This was renamed

the All India Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries (AICCCR), and later

launched the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) as a new revolutionary party, on

April 2, 1969. Charu Mazumdar was its General Secretary. The CPI(M-L) held its first Party

Congress in Kolkata under strict underground conditions in 1970. Mazumdar was re-elected

General Secretary, and the Party Congress put forward its basic programme of protracted

people’s war, including the annihilation (killing) of class enemies.

Of course the Indian ruling class, both

in West Bengal and around the country, mounted a fierce crackdown on this new revolutionary

movement, and this reached a peak during and after 1971 when many key Naxalite leaders

were killed. Mazumdar was apparently betrayed by a renegade Party member, and was arrested

in Kolkata on July 16, 1972. He was taken to Kolkata police headquarters in the Lal Bazar

neighborhood where he underwent the most horrifying and cruel tortures. No one, not even

his family, his lawyer, or a doctor, was allowed to see him. He died at 4 a.m. on July 28,

while in police custody.

Although there were some secondary aspects

of Charu Mazumdar’s precise political line which were in error, including the prescription

that Mao Tse-tung should personally be considered the Chairman not only of the Chinese

Communist Party but also the CPI(M-L), Mazumdar was nevertheless a great revolutionary who

made extremely important contributions to the revolutionary movement in India and the

world. He is a martyr who is rightly well remembered and honored by our revolutionary

movement.

Much of the information

in this entry comes from

http://imp-personalities.blogspot.com/2007/09/charu-majumdar-father-of-naxalism.html

Many of Mazumdar’s political writings can be found in the Marxist Internet Archive at

http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mazumdar/

Dictionary Home Page and Letter Index

MASSLINE.ORG Home Page

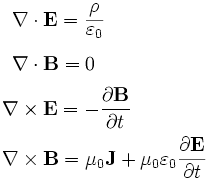

A set of four key equations which collectively organize and describe electromagnetism. The four

individual laws which these equations sum up were actually discovered earlier by other scientists,

but in 1861-62 James Clerk Maxwell brought these laws together in mathematical form in a way which

fully established the unity of electricity and magnetism in a clearer and more profound theoretical

way. Maxwell’s Equations have been formulated in various ways, but the modern method is to

formulate them in terms of partial differential equations in vector calculus, as shown in the

graphic at the right. These four equations represent in turn:

A set of four key equations which collectively organize and describe electromagnetism. The four

individual laws which these equations sum up were actually discovered earlier by other scientists,

but in 1861-62 James Clerk Maxwell brought these laws together in mathematical form in a way which

fully established the unity of electricity and magnetism in a clearer and more profound theoretical

way. Maxwell’s Equations have been formulated in various ways, but the modern method is to

formulate them in terms of partial differential equations in vector calculus, as shown in the

graphic at the right. These four equations represent in turn: [His family name is also often transliterated from Bengali as “Majumdar”.]

[His family name is also often transliterated from Bengali as “Majumdar”.]