Dictionary of Revolutionary Marxism

— O —

OBAMA, Barack (1961- )

President of the United States from January 2009 to January 2017. Since he was the candidate

of the Democratic Party (which many people in the U.S. still naïvely imagine is

qualitatively superior to the other major capitalist party, the Republicans), and because

he was the first Black (African-American) President, many liberals, minorities, and other

people had huge hopes for his presidency—which were slowly dashed against the rocks of

bourgeois reality.

President of the United States from January 2009 to January 2017. Since he was the candidate

of the Democratic Party (which many people in the U.S. still naïvely imagine is

qualitatively superior to the other major capitalist party, the Republicans), and because

he was the first Black (African-American) President, many liberals, minorities, and other

people had huge hopes for his presidency—which were slowly dashed against the rocks of

bourgeois reality.

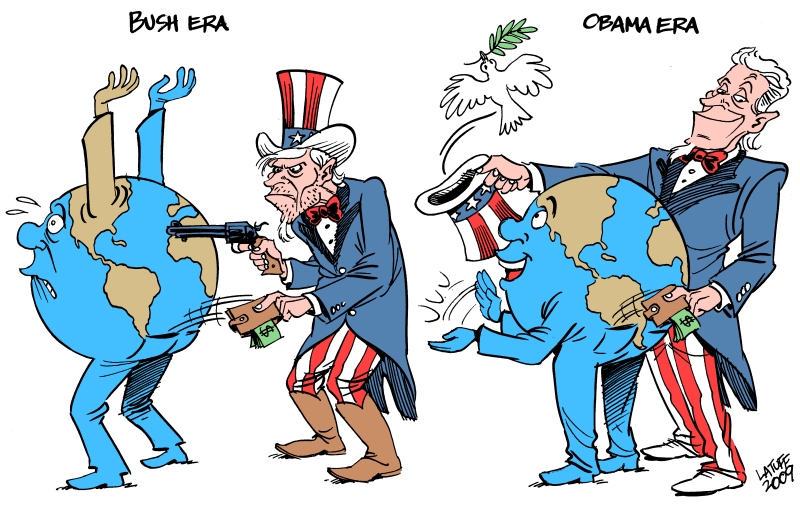

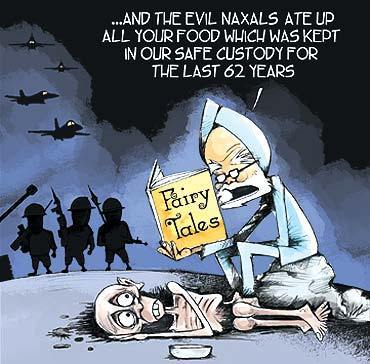

In foreign policy—and despite what the

cartoon at the right hoped for and implied—Obama continued, and to some extent expanded, the

U.S. imperialist wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and extended them further to other countries

such as Syria, Libya and Yemen. He especially promoted the trend toward remote-controlled

mass murder, using armed drones, cruise missiles and bombs dropped

from airplanes in preference to ground troops in these wars. The U.S. war in Afghanistan

which began in 2001, and which Obama promised to end if elected, continued through his

entire 8-year presidency, and still continued after he was out of office. (As of July 2021

this imperialist war has lasted for 20 years, though it is now coming to an official

end—with only much lower levels of U.S. warfare likely to continue in Afghanistan for

now.)

When Obama took office the U.S. and world

were in the beginnings of a severe worsening of the long-developing capitalist financial and

economic crisis, in the form of the Great Recession. As

far as the job situation and welfare of the people is concerned, this intensified economic

crisis still continues. However, following the lead of his predecessor, George Bush, Obama

paid careful attention to bailing out the big banks and other major financial corporations

with many billions of taxpayer dollars. Although a pretense was made by Obama and Congress

in passing legislation (the Dodd-Frank Act) to “prevent” a similar financial crisis from

happening in the future, that was pure window dressing which cannot possibly address the

inherent contradictions within the capitalist mode of production which leads to such

crises.

In trade policy Obama also supported the

interests of capitalist corporations over the U.S. working class. Although he had promised

during the election campaign to reform or abandon the NAFTA agreement, he did nothing of the

kind. (See: NAFTA [McChesney/Nichols quote] )

Instead he arranged for additional international trade deals which eliminated more jobs in

the U.S., and even promoted the worst such proposed trade deal yet, the

“Trans-Pacific Partnership” (which however fell apart once Obama

left office).

The “signature accomplishment” of the Obama

Administration was the grossly inadequate (and quite insufficiently financed)

Affordable Care Act (also known as “ObamaCare”). As

poor as that pathetic excuse for a national health program is, the big debate in American

bourgeois politics since then has been whether ObamaCare should be eliminated (as Republicans

demand) or retained (as Democrats want).

Overall the Obama presidency was a dismal

failure, certainly with regard to advancing the material interests of the working class and

masses, and actually even with respect to significantly advancing the long-term interests of

the ruling bourgeoisie itself! Did the people learn from this negative experience with Obama

to stop supporting ruling class candidates in elections? Unfortunately, no. Many millions of

them still supported either Hillary Clinton or the billionaire demagogue Donald Trump in the

2016 election.

See also:

WHISTLE-BLOWER

[Speaking to a group of leading bankers during the most dangerous period of the Great Recession, when millions of workers were unemployed, losing their homes, etc.] “My administration is the only thing standing between you and the pitchforks.” —President Barack Obama, quoted by Robert Kuttner, “Free Markets, Besieged Citizens”, The New York Review of Books, July 21, 2022, p. 14. [An interesting self-exposure, indeed, about the real role of liberal Democrat politicians in America at the present time: namely, keeping the masses fooled and under control, for the benefit of the rich. —Ed.]

“OBAMA CARE”

See: AFFORDABLE CARE ACT

OBEDIENCE

Obedience “implies compliance with the demands or requests of someone in authority”. [Cf.

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed., 1991)] However, within a genuine

communist party we speak not of “obedience to demands”, but rather of organizational

discipline. Whereas obedience is something that often implies that force or threats

of force are used, organizational discipline within the proletarian party is something

which is voluntarily agreed upon by each new member of the party; it is part of the

rules of democratic centralism which each member of the party agrees to adhere to when they

join.

See also:

DISCIPLINE—Of the Proletarian Party,

DEMOCRATIC CENTRALISM,

JESUITS [Amir Alexander quote]

OBESITY

Being really excessively fat. Obesity is more and more common in advanced capitalist countries, where

there is an ongoing general decline in people’s health and physical condition. According to the

Centers for Disease Control, adult men (age 20 and older) in the United States weigh an average of

200 pounds. For women, the average is 171 pounds. Fully 73.6 percent of American adults are classified

as “overweight” and 42.5 percent are “obese.” [These are pre-pandemic figures; the situation is probably

even worse now. See:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/body-measurements.htm for some more details.] That means

that over 80 million people in the U.S. are now obese. However, obesity is fairly common in

“Third World” countries too, often because of the very poor quality

diets available to people.

Being really excessively fat. Obesity is more and more common in advanced capitalist countries, where

there is an ongoing general decline in people’s health and physical condition. According to the

Centers for Disease Control, adult men (age 20 and older) in the United States weigh an average of

200 pounds. For women, the average is 171 pounds. Fully 73.6 percent of American adults are classified

as “overweight” and 42.5 percent are “obese.” [These are pre-pandemic figures; the situation is probably

even worse now. See:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/body-measurements.htm for some more details.] That means

that over 80 million people in the U.S. are now obese. However, obesity is fairly common in

“Third World” countries too, often because of the very poor quality

diets available to people.

In an ultra-individualist, and bourgeois country like

the United States, it is considered terribly improper to suggest to fat or obese people that it might

be a good idea for them to lose some weight. And any hint of criticism of someone for being obese is

condemned as “fat-shaming”.

OBJECTIVE REALITY

The real world as it actually is, as opposed to various ideas—often quite fanciful—about the

world. Also called the external world, especially in older

philosophical writings.

See also:

REFLECTION THEORY

“The laws of war, like the laws governing all other things, are reflections in our minds of objective realities; everything outside the mind is objective reality.” —Mao, “Problems of Strategy in China’s Revolutionary War” (Dec. 1936), SW 1:190.

OBJECTIVE SITUATION

1. [Narrow definition:] The actual political

and/or military situation with regard to all the relevant factors for victory other than

the subjective understanding and attitudes of the Party members, soldiers, and the

advanced forces and the proletariat more generally. In a military situation this would include

the number and quality of the armaments on each side, as well as the fitness of the troops,

the availability of food and supplies, etc.

2. [Broad definition:] The actual political

and/or military situation with regard to all the relevant factors including the subjective

understanding, morale and attitudes of the Party, troops, advanced forces, proletariat as

a whole, etc.

The idea here is that sometimes we want to

contrast, or consider separately, the material and ideological factors in a struggle, while

at other times we just want to think about all the relevant factors for victory—both

“objective” and “subjective”—for both sides in a struggle. Although there is obviously

grounds for confusion between these two opposed definitions, the context soon clarifies which

sense is meant.

See also:

INVESTIGATION—Before Launching Political

Action,

LOOKING AND SEEING

“OBJECTIVISM”

The name the vulgar bourgeois writer Ayn Rand gave to her

shallow philosophical system glorifying selfishness and capitalism.

OBLIGATION

[Ethics:] A moral requirement to act in a certain way. Kant held

the extreme position that (what he took to be) moral obligations are absolute, that is,

they are morally necessary regardless of the consequences.

See also:

CONSEQUENTIALISM,

DUTY

OBLIVIOUSNESS

See: LOOKING AND SEEING

OBSHCHINA

Russian term for semi-feudal peasant village communes, which however, also had certain

collectivist aspects to them. For more about them see:

VILLAGE COMMUNE (Russia)

OCCAM’S RAZOR

A principle enunciated in cryptic form by the medieval philosopher William of Occam (or

Ockham) which states that you should always choose the simplest explanation for any

phenomenon, the one requiring the fewest assumptions and supporting entities.

See also:

Philosophical doggerel on

Occam and his “razor”.

OCCASIONALISM

A religious idealist doctrine which arose in the 17th century as an attempt to explain

the mysterious interaction of “soul” and body, as required by

Descartes’s dualistic theory

of the world. The Occasionalists held that the reciprocal action between mind and body

is due to the intervention of God. Malebranche carried this idea to the further extreme

of postulating divine intervention in every single causal action.

Of course from the dialectical materialist

point of view there are no “souls”, and mental phenomena are merely high-level ways of

looking at the functioning of certain very complex material systems (e.g. brains). Thus

the supposed mystery of how “two totally independent things”, mind and brain, can interact

and influence each other does not arise.

See also:

PSYCHOPHYSICAL PARALLELISM

OCCUPY MOVEMENT

The “Occupy Movement” was an international youth-based leftwing populist political movement that,

though it arose from earlier protests around the world against the rich, their corporations, and

in favor of genuine democracy and social justice, became an international sensation with the

advent of the massive Occupy Wall Street demonstrations in Zuccotti Park, Lower Manhattan,

beginning on September 17, 2011. The movement then spread like wildfire, and by October 9th Occupy

protests had occurred and were often actively continuing and growing in more than 600 locations

in the United States, and in more than 951 places in 82 countries. [Much of the specific

information here comes from the Wikipedia.]

The “Occupy Movement” was an international youth-based leftwing populist political movement that,

though it arose from earlier protests around the world against the rich, their corporations, and

in favor of genuine democracy and social justice, became an international sensation with the

advent of the massive Occupy Wall Street demonstrations in Zuccotti Park, Lower Manhattan,

beginning on September 17, 2011. The movement then spread like wildfire, and by October 9th Occupy

protests had occurred and were often actively continuing and growing in more than 600 locations

in the United States, and in more than 951 places in 82 countries. [Much of the specific

information here comes from the Wikipedia.]

Of course the rise of such huge democratic

movements by the masses, no matter how peaceful they were in actual fact, hugely alarmed the

capitalist ruling classes in the U.S. and elsewhere, and after a month or so, when it became

apparent to the rulers that the Occupy Movement was not going away on its own, the authorities

clamped down and began forcibly removing the “Occupations”, and arresting anyone who resisted

or protested. One of the first police attacks on peaceful encampments was against the Occupy

Oakland site on October 25, 2011. By the end of that year almost all Occupy camps had been raided

and broken up, with the last of the high-profile sites, in Washington, D.C., and in London,

evicted by February 2012, according to the Wikipedia.

The Occupy Movement tried to take mass democracy

seriously, though some of the more anarchist-type ideologues involved in it had naïve

conceptions about how “direct democracy” might actually be

achieved without any form of representation being involved. The slogan “We are the 99%”

and the corresponding identification of the enemy of the movement as “the One Percent”, was,

however, positively brilliant! In effect it gave a new, alternative name to the bourgeoisie,

the capitalist ruling class, which everyone could immediately and instinctively see was entirely

appropriate! And, because of the Occupy Movement, the enemy of the masses has thus been more

clearly identified to the people.

See also:

HORIZONTALIDAD,

HORIZONTALISM,

PUBLIC RELATIONS

“In 2011, Occupy Movement protesters at Zuccotti Park, in Lower Manhattan, were not allowed to use bullhorns, so they repeated, telephone-style, phrase by phrase, a speech given at one end of the park so people could hear it at the other.” —New York Times, “What Made 42nd Street Soar”, September 28, 2020.

OCEANS

See also below and,

POLLUTION — Of the Oceans

OCEAN RESOURCES

See:

SOVIET UNION—Ocean Fishing Industry

OCEAN SHIPPING

“90% of world trade moves on water.

“In 2019, 11.1 billion tons of goods were

moved across the world’s oceans. And according to the World Shipping Council, the liner industry

moves more than $4 trillion in goods annually.” —Brad Howard, CNBC.com, July 2, 2021.

[This video program went on to discuss why

there was in the summer of 2021 a serious container ship traffic jam causing shipping delays

around the world. These problems include the continuing after-effects of the massive container

ship “Ever Given” which blocked the Suez Canal in March 2021, port disruptions because of the

Covid-19 Pandemic, and the tendencies for disruptions in one port to then affect other ports in

a sort of chain reaction. And since to increase profits the capitalist world economy has largely

moved to the paradigm of “just-in-time production”, these shipping delays in the global trade

network have become a major factor leading to more production interruptions and shortages of key

commodities. There really is some truth to the idea that capitalist production is anarchic and

thus subject to problems and interruptions of its own making. —Ed.]

OCTOBER LEAGUE

A short-lived organization in the U.S. “New Communist Movement” of the early 1970s which

developed out of one part of the RYM II faction of

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and later transformed itself

into the so-called Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist). OL was

characterized by the combination of arrogance and ideological instability that was quite

common within the general primitiveness of the reborn revolutionary movement of that era. The

top leader of both OL and the CP(ML) was Michael Klonsky,

who later abandoned “Marxism” entirely—even in its totally revisionist perverted form.

OCTOBER REVOLUTION

Also known as the Bolshevik Revolution. It

occurred November 8, 1917, which was October 25 on the calendar then in use in

Russia. [More to be added...]

OCTOBER ROAD

The term “October Road” is shorthand for the revolutionary

strategy, tactics and policies followed by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution;

sometimes just for the strategy used in the October Revolution insurrectionary seizure of power

itself, but often for the whole Bolshevik revolutionary strategy over a period of more than two

decades starting from around 1900. Thus the question “To what degree should American revolutionaries

follow the October Road?” means “To what degree should we employ the revolutionary strategy and

tactics that Lenin and the Bolsheviks used in making revolution?” This of course is still an open

question, though obviously revolutionaries in advanced capitalist countries have much to learn from

and emulate in the Bolshevik Revolution.

See also:

INSURRECTION

[Lenin speaking of the revolutionary strategy and tactics of the Bolsheviks at the time of the First World War (and note that he just uses the word ‘tactics’ where we would today usually say ‘strategy’):] “The Bolsheviks’ tactics were correct; they were the only internationalist tactics, because they were based, not on the cowardly fear of a world revolution, not on a philistine ‘lack of faith’ in it, not on the narrow nationalist desire to protect one’s ‘own’ fatherland (the fatherland of one’s own bourgeoisie), while not ‘giving a damn’ about all the rest, but on a correct (and, before the war and before the apostasy of the social-chauvinists and social-pacifists, a universally accepted) estimation of the revolutionary situation in Europe. These tactics were the only internationalist tactics, because they did the utmost possible in one country for the development, support and awakening of the revolution in all countries. These tactics have been justified by their enormous success, for Bolshevism (not by any means because of the merits of of the Russian Bolsheviks, but because of the most profound sympathy of the people everywhere for tactics that are revolutionary in practice) has become world Bolshevism, has produced an idea, a theory, a programme and tactics which differ concretely and in practice from those of social-chauvinism and social-pacifism.” —Lenin, “Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky” (Oct.-Nov. 1918), LCW 28:292.

“... the mass of workers in all countries are realizing more and more clearly every day that Bolshevism has indicated the right road of escape from the horrors of war and imperialism, that Bolshevism can serve as a model of tactics for all.” —Lenin, ibid., LCW 28:293. (As always in this Dictionary, italics and other emphasis are as they appear in the original.)

OCTOPUS

Short for Organization for Counter-Terrorism and Operations. This is yet another

government paramilitary force attempting to destroy the Naxalites

(Maoist revolutionaries) in India. This particular force seems to have been set up by the

Andhra Pradesh state government.

OECD

See: ORGANIZATION FOR ECONOMIC COOPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT

OFFICE OF POLICY COORDINATION (Of the U.S. State Department)

Despite its purposely bland name, this was a secret United States “black ops” (covert

operations) spy agency hidden within the State Department bureaucracy in the period after the

World War II era Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was disbanded. When the

Central Intelligence Agency was first established in 1947, it mostly

functioned—as its name suggests—as merely a centralizing agency for all the extensive spying

done by the many U.S. spy agencies. Alan Dulles, though not a government employee at the time,

played a key role in establishing the OPC as a covert operations agency. And when he later

became head of the CIA the sort of “dirty tricks” and criminal activities characteristic of

the OPC were transferred to the CIA.

See also:

OPERATION SPLINTER FACTOR

OFFICE OF STRATEGIC SERVICES

The U.S. government spy agency which existed during World War II; the primary forerunner of

the CIA which was established in 1947.

OFFICE SPACE

A measure of the average cost of renting commercial office space in a city or section of it

(i.e., the “downtown area”), usually given in terms of some unit area (such as per square

foot). The change of the price of office space is an economic indicator of whether

the capitalist economy is expanding or declining, and whether or not there is a

property bubble developing in the price of business

buildings.

“Office space now costs more in Beijing than it does in New York. Rents have soared in Beijing over the past two years, making it the fifth most expensive city in the world for commercial space, surpassing New York. Hong Kong remains the most expensive, followed by London, Tokyo, and Moscow.” —From a Financial Times report quoted in The Week, Feb. 17, 2012, p. 38. [This is another indication that the property bubble in China has expanded to quite dangerous levels. And as long as the office space price remains high the commercial property bubble will keep expanding. —S.H.]

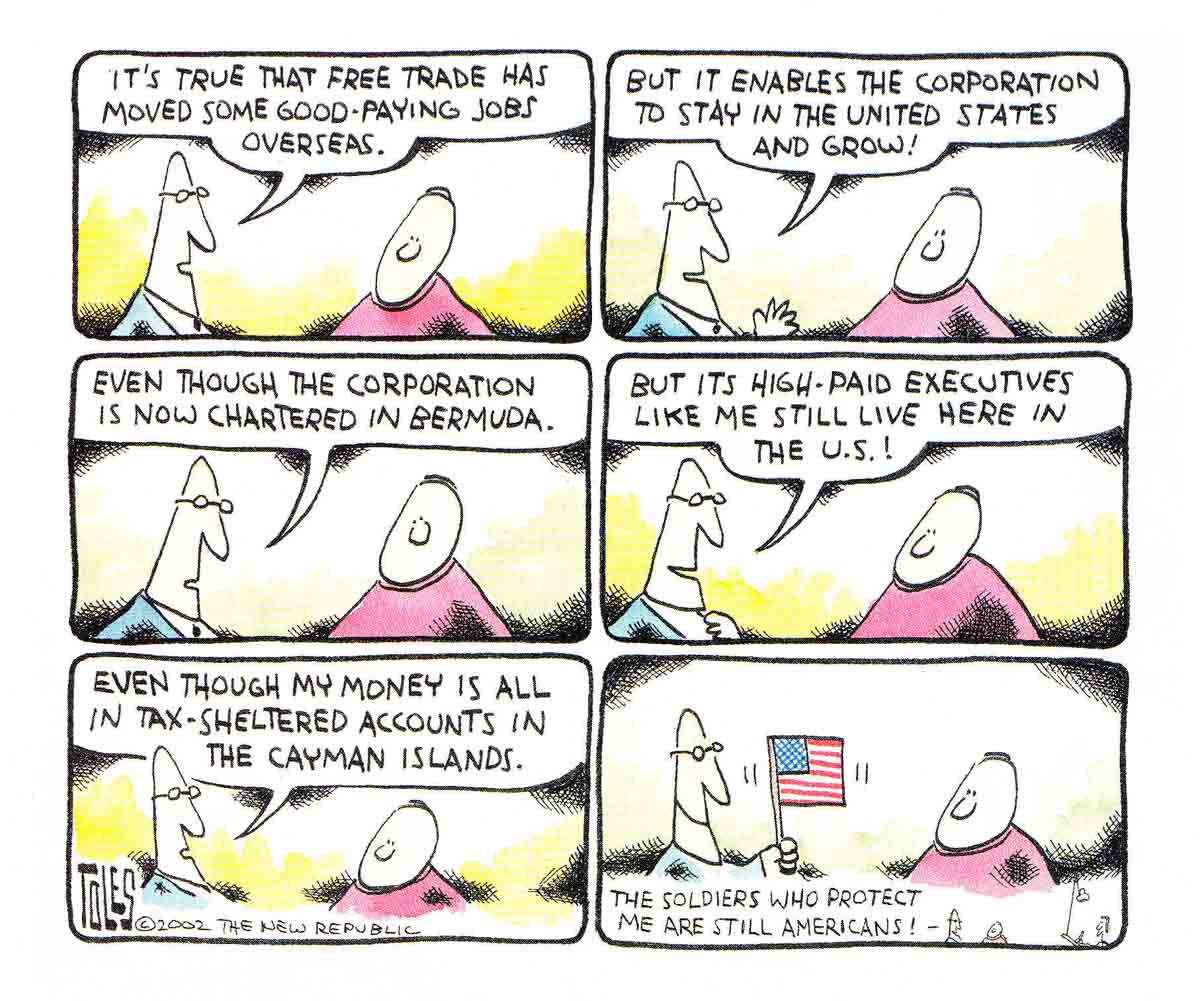

OFFSHORING

The transfer of jobs by a multinational corporation from its home country to other, lower-wage

countries. This term is popular in the bourgeois press in the United States where the transfer

of jobs to other countries usually means overseas countries, though many jobs have also

been shifted to Mexico. In the cartoon at the right, this offshoring is referred to under the more

general term, “free trade”, which often includes a lot of offshoring as a prelude to increased

trade between countries. (As production is shifted to other countries, a good part of the goods

produced then need to be imported back into the United States. However, if tariffs are too high,

and destroy “free trade”, it is then no longer profitable to shift production to other countries.

Thus offshoring and free trade are related and interdependent processes.)

A job is considered to be offshorable

if it would be both easy to transfer it to another country and profitable for the employer to

do so. According to an August 2009 study by two bourgeois economists, Alan Blinder and Alan

Krueger, despite all the jobs which have already been shifted out of the country, roughly

one out of four remaining U.S. jobs are offshorable. “Perhaps most surprisingly, routine work

is no more offshorable than other work.” Moreover, the jobs of well educated workers are

somewhat more likely to be offshorable than those of poorly educated workers.

See also:

RESHORING

OGALLALA AQUIFER

See:

AQUIFER

See:

AQUIFER

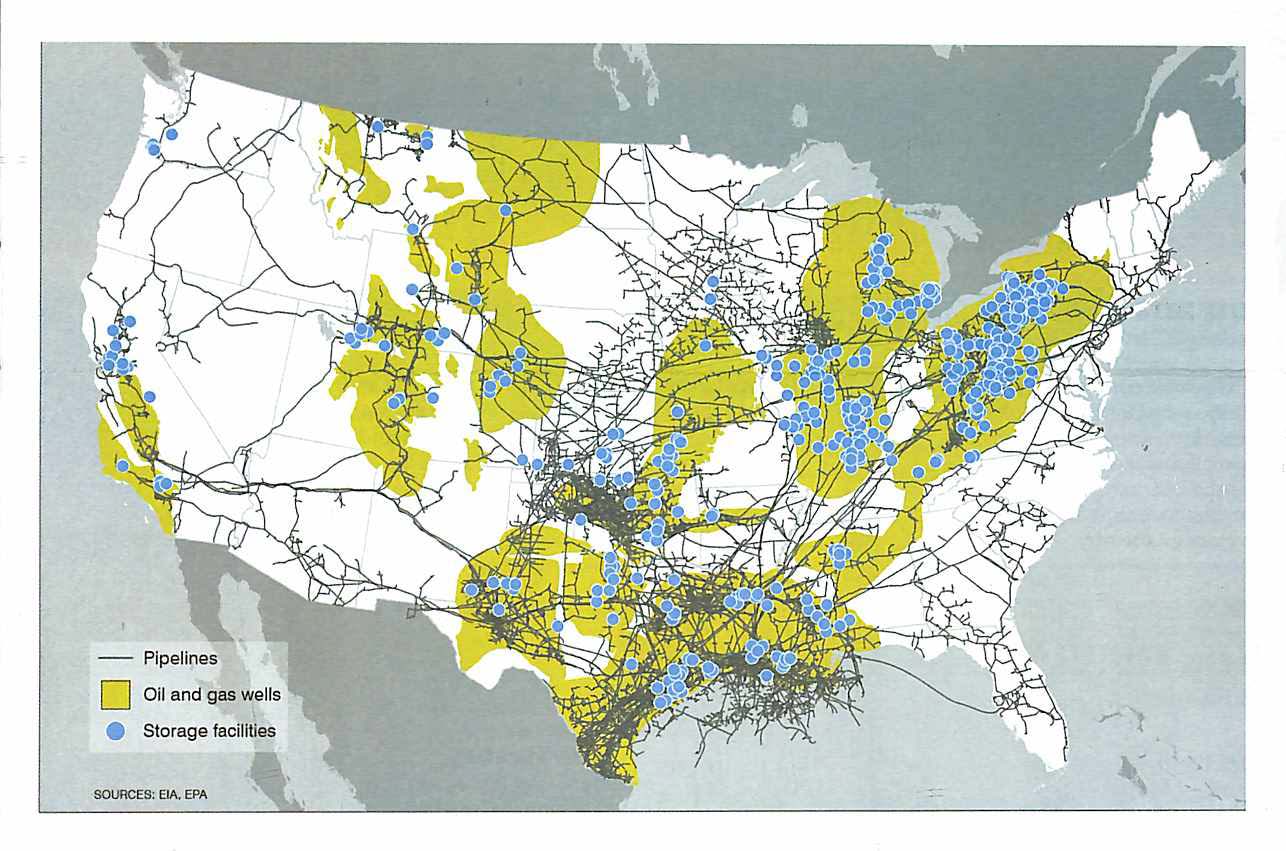

OIL AND GAS FIELDS AND PIPELINES (U.S.)

The map at the right (prepared by the liberal Environmental Defense Fund, c. 2016) shows the locations

in the United States of oil and gas fields, storage facilities, and pipelines. These very extensive

areas are of course extremely vulnerable to serious pollution due not only to major spills and other

accidents, but also through the very leaky and messy normal daily operations by the capitalist

corporations owning them, who care far more about their profits than they do about any harm to the

people or the planet. The EDF notes that “there are 1.3 million active oil and gas wells in the U.S.

and 305,000 miles of natural gas pipeline, and that 9.3 million metric tons of methane escape each

year. That is the same 20-year climate impact as more than 200 coal-fired power plants.”

OIL & GAS INDUSTRY — Productivity In

“The companies that extract, transport and process oil and gas employ roughly 25 percent fewer workers than they did a decade earlier when they were churning out less fuel, according to a Times analysis.” —New York Times, “For Oil Companies, More Production and Fewer Jobs”, January 28, 2025. [In other words, pretty much the same as in most other industries! —Ed.]

OIL PRICES

“As a rule of thumb, a $10 rise in the cost of a barrel of oil translates to a 24-cent rise in the cost of a gallon of gasoline.” —New York Times, National Edition, “After Fears of Recession, New Crises”, Oct. 4, 2024.

OIL WELLS

“As many as 3.9 million abandoned and aging oil wells dot the United States, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.” —New York Times, National Edition, May 28, 2024, p. 3.

“Scientists have found that abandoned oil wells, often called ‘orphaned’ wells, release methane, a powerful greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change, as well as benzene, a chemical linked to leukemia and other blood cancers.” —New York Times, “Facts of Interest”, November 1, 2025.

OKHRANA

The agency of the secret political police in Tsarist Russia,

which was formed in order to try to suppress and destroy the revolutionary movement. It hounded,

arrested, exiled, imprisoned or killed many thousands of revolutionaries. Although there were a

few well publicized assassinations of Tsars and Tsarist agents, overall the Okhrana was quite

effective until revolutionaries themselves began to use more sophisticated methods to secretly

organize themselves, and organize the working class to fight back, and until the conditions of

the masses became so extremely bad that even constant vicious police oppression could not keep

them from rebelling.

See also:

MALINOVSKY, Roman

OKISHIO THEOREM

A mathematics-based theorem in theoretical political economy, first formulated by the Japanese

Marxist/Neo-Ricardian economist Nobuo Okishio in 1961,

which does seem to show that, given some reasonable assumptions, the idea that there is a long-term

tendency for the rate of profit to fall [or TRPF] under capitalism, because of technological

change, is simply not correct. In his paper Okishio argued that “if the newly introduced technique

satisfies the cost criterion [i.e. if it reduces unit costs, given current prices] and the rate of

real wage remains constant”, then the rate of profit must increase, not only for that one

company, but for the industry and economy averages as a whole!

The Okishio Theorem itself has been proven

mathematically. But, as is often the case in science, the actual social implications,

economic and otherwise, that should be viewed as having been totally established by this proof are

still subject to dispute. If, as seems to be fairly plausible, this theorem demonstrates what it

claims to demonstrate, it either proves, or at least very strongly implies, that one of the

three theories that Marx advanced as being the basic cause of the recurring capitalist economic

crises, namely the “Falling Rate of Profit Theory”,

also cannot be correct. (Although there are plenty of other reasons to question the Falling Rate of

Profit Theory, even if the Okishio Theorem is eventually shown to be irrelevant.) However, the

Okishio Theorem has caused tremendous consternation among those who favor this explanation for

capitalist economic crises. The theorem may also have some consequences for the precise formulation

of the labor theory of value as well.

We should immediately note that, however valid the

Okishio Theorem actually is, Marx’s more basic explanation of capitalist economic crises in terms of

overproduction in comparison with market demand remains

completely valid. And similarly, the most essential aspects of the labor theory of value, arising

from the obvious fact that all wealth derives from human labor acting on the natural products of the

world around us, remain completely and absolutely true.

A more thorough discussion of the Okishio Theorem,

including its mathematics, Neo-Ricardian framework, and conditional assumptions, can be found on the

Wikipedia at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okishio%27s_theorem Excerpts from that article, focusing

on various Marxist (or pseudo-Marxist) reactions to the theorem, are given below.

“Okishio’s theorem ... has had a major impact on debates about Marx’s theory

of value. Intuitively, it can be understood as saying that if one capitalist raises his profits

by introducing a new technique that cuts his costs, the collective or general rate of profit in

society goes up for all capitalists. In 1961, Okishio established this theorem under the

assumption that the real wage remains constant. Thus, the theorem isolates the effect of pure

innovation from any consequent changes in the wage.

“For this reason the theorem, first proposed

in 1961, excited great interest and controversy because, according to Okishio, it contradicts Marx’s

law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Marx had claimed that the new general rate of

profit, after a new technique has spread throughout the branch where it has been introduced, would

be lower than before. In modern words, the capitalists would be caught in a rationality trap or

prisoner’s dilemma: that which is rational from the point of view of a single capitalist, turns out

to be irrational for the system as a whole, for the collective of all capitalists. This result was

widely understood, including by Marx himself, as establishing that capitalism contained inherent

limits to its own success. Okishio’s theorem was therefore received in the West as establishing

that Marx’s proof of this fundamental result was inconsistent.

[BannedThought.net editorial insertion: While

if the ‘falling rate of profit’ notion is not correct, this does remove one reason for

thinking that capitalism is doomed, there are still many other reasons to strongly believe so,

including the fact that in the capitalist-imperialist era this socioeconomic system can no longer

resolve and end major depressions except through ever-more destructive world wars! This is a

consequence of Marx’s basic overproduction theory, rather than the falling rate of profit theory

for crises. —Ed.]

“More precisely, the theorem says that the

general rate of profit in the economy as a whole will be higher if a new technique of production is

introduced in which, at the prices prevailing at the time that the change is introduced, the unit

cost of output in one industry is less than the pre-change unit cost. The theorem, as Okishio points

out, does not apply to non-basic branches of industry.

“The proof of the theorem may be most easily

understood as an application of the Perron–Frobenius theorem. This latter theorem comes from a

branch of linear algebra known as the theory of nonnegative matrices. A good source text for the

basic theory is Seneta (1973). The statement of Okishio’s theorem, and the controversies surrounding

it, may however be understood intuitively without reference to, or in-depth knowledge of, the

Perron–Frobenius theorem or the general theory of nonnegative matrices....

“Some Marxists simply dropped the law of the

tendency of the rate of profit to fall, claiming that there are enough other reasons to criticize

capitalism, that the tendency for crises can be established without the law, so that it is not an

essential feature of Marx’s economic theory. Others would say that the law helps to explain the

recurrent cycle of crises, but cannot be used as a tool to explain the long term developments of

the capitalist economy....”

—Wikipedia (accessed on March 27, 2023).

“OKUN’S LAW”

An empirically derived rule of thumb in bourgeois economics that GDP growth must be at least

3% per year in order to reduce the prevailing rate of unemployment.

Another of the various formulations of the

“law”, known as the “gap version”, is that for every 1% increase in the unemployment rate a

country’s GDP will settle at roughly another 2% lower than its

“potential output”. This “law” was proposed by Arthur

M. Okun in 1962, and since then its reliability has often been disputed.

OLBERS’ PARADOX

The supposed “paradox” named after the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers in which the universe

was assumed to have an infinite number of stars, and therefore in which every single line of sight from

the Earth should eventually come to a star—and yet, because the sky is mostly dark at night, this

doesn’t seem to be the case.

For further discussion, see:

DARKNESS AT NIGHT

OLD AGE CARE WORK

“As jobs have shifted into areas like health care and retail, employers have

taken advantage of the permissive landscape. The part of the economy that is now expanding most

quickly is the work of caring for aging baby boomers. Half of the ten occupations projected to

add the most jobs in the United States by 2026 are different ways of saying ‘nurse.’ Those jobs

tend to be physically demanding and emotionally draining; they also tend to be poorly paid,

with meager benefits and little job security. The line of work projected to add the most jobs

over the next decade, ‘personal care aides,’ offered an average annual salary of $23,100 in

2016.

“If the iconic workplace of the midcentury

was an automobile factory that lifted its workers into the middle class, the microcosm of the

modern economy is a hospital staffed by a handful of highly paid physicians and a vast army of

poorly paid support staff.”

—Binyamin Appelbaum, The Economists’

Hour: False Prophets, Free Markets, and the Fracture of Society (2019), pp. 326-7.

OLD PEOPLE

Or, more euphemistically, “seniors”. Over the centuries, as medical science and social conditions have

at least in general improved, what counts as being “old” has gradually increased. Whereas someone aged

50 might centuries ago been considered old, they might now be viewed as merely “middle aged”.

See also:

AGING,

LIFE EXPECTANCY

“The proportion of people over age 65 living in poverty jumped to 14.1 percent last year from 10.7 percent in 2021 and 9.5 percent in 2020.” —New York Times, National Edition, Oct. 3, 2023, p. 3.

OLD REVOLUTIONARIES

“When you get old you want to teach.” —Maxim Gorky, quoted in Moissaye

Olgin, “Maxim Gorky: Writer and Revolutionist” (1933), p. 62.

[It is true that old revolutionaries do

often have a certain amount of hard-won wisdom to impart to younger people. But, more generally,

what old revolutionaries can and should do is the same as what they did when younger, though in

smaller and somewhat less frequent contributions as befits their reduced capabilities. —Ed.]

OLIGARCHY

Rule by the few, usually for their own corrupt and selfish purposes. Thus often, in

effect, rule by the few who are rich. Bourgeois society, whether in the form of

bourgeois democracy or

fascism, should be considered a type of oligarchy since

the ruling bourgeoisie is a tiny class relative to the

whole population.

OLIGOPOLY

Semi-monopoly, or a “looser form” of monopoly. In other words,

a situation where a small number of producers control the capitalist market for some

commodity, and limit their competition either in all respects (definitely including prices),

or—more commonly today because of the nominal anti-trust

laws—to areas of styling and advertising.

Lenin, when he talked about monopoly,

was really using the term in a way which would today better be called oligopoly.

(The word ‘oligopoly’ did not enter the English language until 1895 and even then at first

only in technical publications, and the Russian equivalent probably also did not exist

when Lenin was writing.)

ONE-CHILD POLICY (in China)

The Chinese government policy restricting most urban families to just one child. This policy

was introduced in 1978-79, after the Mao era, and by 2016 is finally being gradually phased

out. The government said that as of 2015 35.9% of the population was subject to this

one-child limit per family (with most of the rest being subject to a two-child limit). It

estimated that without this policy there would have been 250 million more babies born by the

year 2000.

At the time of the establishment of the

People’s Republic of China in 1949, Mao and the other revolutionary leaders initially viewed

having a large and rapidly growing population as an asset. But this opinion soon changed and

in August 1956 the Ministry of Public Health began vigorously supporting mass birth control

efforts. However, the fertility rate remained high, and after a few years a new campaign to

encourage later marriage and a lower birth rate was implemented. During the period of 1963-66

this cut the birth rate to half its previous level.

For a few years, with the advent of the

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the more urgent matter of

which class would control society became preeminent. But in 1972-73 the People’s government

began a new nationwide birth control campaign. In the countryside the

“barefoot doctors” distributed birth control information

and contraceptives to the members of the people’s communes. In the mid-1970s the government

recommended that the maximum family size should be 2 children in urban areas and 3 or 4 in

the countryside. Mao himself was personally identified with the family planning movement at

this time. Still, the means used while Mao was alive was generally the

mass line method of democratic persuasion, and not one of

enforcement of small family size through fines or other penalties.

Once the revisionists seized control and

began to move the country back into capitalism, the whole point of family planning changed.

It was no longer a matter of how best to improve the welfare of all the people, but

rather of promoting the expansion of capitalist production as fast as possible and promoting

the growth of the economic and political power of the new bourgeoisie. What desire remained

to promote improved living standards for the masses was mostly for the purpose of keeping

them from challenging the new capitalist ruling class. And the methods used to promote

family planning became much more bureaucratic, legalistic and even authoritarian.

While education and social pressure are still

also used to promote the one-child policy, there are now considerable economic penalties

for violators, and sometimes strong coercion, including even forced abortions and

sterilizations. Moreover, the manner in which the policy has been implemented has led to many

cases of female infanticide. The traditional backward desire of Chinese families (especially

in rural areas) for a male heir, which has led to these problems, has not been sufficiently

combatted by educational campaigns, and this is now resulting in a growing disproportionate

shortage of women in Chinese society.

While the goal of promoting a low birth

rate in China, just as elsewhere in the world, is laudable, the manner in which the one-child

policy has been implemented cannot be supported. Somewhat surprisingly, a fairly large

majority of people in China do support the policy (one poll around 2008 claimed that 76% do),

though there also seem to be growing numbers of those ignoring it. Most interestingly of all,

there are now suggestions by bourgeois economists in both China and overseas, that this

one-child policy is no longer in the interests of Chinese capitalism. The idea is that it

“unduly” limits the growth of the cheap labor supply and the size of the domestic market, and

also leads to an aging population which on average consumes less. This appears to be a major

factor in why the policy is now being phased out.

In the fall of 2013 the one-child policy was

slightly weakened. Previously married couples, both of whom were a single child, were allowed

to have two children. Now, if just one of them was a single child, they are allowed to have

two children. In 2015 the “one-child policy” was weakened much more and will probably be

completely replaced by a universal “two-child” policy soon.

[Some of the information in this entry comes

from the Wikipedia.]

“China’s birth rate on the rise

“China’s birth rate rose last year

to its highest point since 2000, following the relaxation of the country’s one-child

policy in 2015. There were 17.86 million births in China last year, a 7.9% increase

from 2015.” —Time magazine, Feb. 6, 2017, p. 12.

ONE-DIVIDES-INTO-TWO STRUGGLE (In Maoist China)

The “One Divides into Two” controversy (一分为二) was a philosophical struggle in China beginning in

1964 over opposing ideas about how dialectical

contradictions develop and resolve themselves. The proper way to understand this specific point is

that of Lenin and Mao (see the separate One-Into-Two entry below). However,

the nominally (but phony) Marxist philosopher Yang Xianzhen in China came up with the erroneous notion that

the primary law of dialectics is that “Two Unite into One” (or “Two Combine into One”). Or, in other words,

that development supposedly proceeds through the peaceful unification of the dialectical opposites. This

is directly opposed to the Leninist and Maoist conception of “one dividing into two” and with one aspect of

a contradiction overpowering the opposing aspect. Yang’s notion was clearly anti-dialectical. Worse yet,

it can be, and was, used to support a number of reactionary and pro-capitalist ideas, such as that class

struggle should be minimized or abandoned in contemporary socialist society, and that capitalist economic

measures can be used to “build socialism”. The “Two Unite into One” idea, therefore, was very popular with

the capitalist roaders.

The fine Maoist philosopher Ai

Siqi launched a powerful attack on Yang Xianzhen’s reactionary conception, and was soon followed by Mao

himself. Numerous other critics of Yang then came forward, and his theory was completely rejected by the

Communist Party of China while Mao was alive.

Yang Xianzhen was rehabilitated by the capitalist roaders

after their coup d’état following Mao’s death, and his “two unite into one” perversion of “Marxist

dialectics” was wholeheartedly embraced.

For a large number of contemporary articles (in both English

and Chinese) about this struggle in Maoist China, and its aftermath, see:

http://marxistphilosophy.org/ChinTrans1221.htm

“Richard Baum has put the [one-divides-into-two] controversy in terms of modern game

theory as a debate between zero sum and non-zero sum competition. Alain Badiou during his Maoist phase

would use the principle of One Divides into Two to criticize the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze.”

—Wikipedia article on “One_Divides_into_Two” (as of June 29, 2020).

[Baum is a bourgeois Sinologist, and his absurd

“interpretation” of the One Divides into Two struggle is a typical example of their distortions. The

off-the-wall use of Maoist phrases by Badiou to attack other French idealist philosophical phonies is

even more bizarre! —Ed.]

ONE-INTO-TWO

A core viewpoint in dialectics, which sums up two main

principles: 1) Everything in the world is in reality a unity of opposites, or (dialectical)

contradiction of opposing forces; and

2) Development consists of the dialectical resolution of such

contradictions, or in other words, in the splitting of this unity, and the triumph of one

opposing aspect over the other, thus transforming the basic nature of the original entity.

See also:

ONE-DIVIDES-INTO-TWO STRUGGLE above.

“The splitting of a single whole and the cognition of its contradictory

parts ... is the essence (one of the ‘essentials,’ one of the principal, if not

the principal, characteristics or features) of dialectics. That is precisely how Hegel,

too, puts the matter...

“The correctness of this aspect of

the content of dialectics must be tested by the history of science. This aspect of

dialectics (e.g., in Plekhanov) usually receives inadequate attention: the identity of

opposites is taken as the sum-total of examples ... and not as a law of

cognition (and as a law of the objective world)....

“The identity of opposites (it

would be more correct, perhaps, to say their ‘unity,’—although the difference between

the terms identity and unity is not particularly important here. In a certain sense both

are correct) is the recognition (discovery) of the contradictory, mutually exclusive,

opposite tendencies in all phenomena and processes of nature (including mind

and society). The condition for the knowledge of all processes of the world in their

‘self-movement,’ in their spontaneous development, in their real life, is the

knowledge of them as a unity of opposites. Development is the ‘struggle’ of opposites....

“The unity (coincidence, identity,

equal action) of opposites is conditional, temporary, transitory, relative. The struggle

of mutually exclusive opposites is absolute, just as development and motion are absolute.”

—Lenin, “On the Question of Dialectics” (1915), LCW 38:359-360.

“ONE PERCENT” or “THE ONE PERCENT”

A term introduced by the recent Occupy Movement in the U.S. to

refer to the class of very rich people who run the country. It is, in short, a euphemism for

the bourgeoisie. However, in the U.S. the level of class consciousness is so abysmally low that

Marxist terminology (such as the bourgeoisie or even the capitalist class) is

either not understood by most people, or else often sounds to their ears like “obsolete” or

“politically suspicious” jargon! In this situation, the introduction of a new term for the

bourgeoisie was in fact quite useful! Of course, it is up to us Marxists to further explicate

rather vague terms such as “the one percent” and to get people to understand and get used to the

terminology that has been developed in our revolutionary science of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.

See also:

MILLIONAIRES

ONE-SIDEDNESS

See:

POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE

ONE STEP FORWARD, TWO STEPS BACK [Lenin]

Important 1904 political pamphlet by Lenin focusing on the appropriate organization and line

of a revolutionary communist political party.

“This book is of key importance in establishing the principles of

organization of the Communist Party. It was written in 1904 following the 2nd Congress

of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party—the Congress at which the split between

the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks first showed itself.

“In order to understand this book

and its background, the reader should consult the History of the Communist Party of

the Soviet Union, Chapter II, Sections 3 and 4. At the 2nd Congress in 1903, two

opposed groups became apparent in the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, revolutionary

and opportunist. After the adoption of the Party Programme there took place a dispute

over the Party Rules. Lenin and his followers held that there should be three conditions

for party membership:

(1) Acceptance

of the programme.

(2) Payment of

dues.

(3) Belonging

to a party organization.

His opponents held that condition (3) was not necessary.

“At the end of this Congress the

followers of Lenin gained a majority on the Central Committee and on the Editorial Board

of the party newspaper Iskra. They therefore became known as the Bolsheviks—from

the Russian word meaning ‘Majority’—while the others were known as Mensheviks—from the

Russian word for ‘Minority.’ But afterwards the Mensheviks managed to capture Iskra

and began an attack on the party organization, which they declared was too ‘rigid.’ They

wanted ‘liberty’ for individuals not to obey party decisions. The opportunists thus began

their operations by an attack on the principles of party organization.

“Lenin recognized that this attempt

to weaken the party organization was a prelude to imposing opportunist policies on the

party concerning the major political issues. In One Step Forward, Two Steps Back,

after analyzing the proceedings and the votes at the 2nd Congress, and demonstrating the

existence of two wings—a revolutionary and an opportunist wing—Lenin shows the need for

a disciplined centralized party of the working class.”

—Readers’ Guide to the Marxist

Classics, prepared and edited by Maurice Cornforth, (London: 1953), p. 48.

“ONTOGENY RECAPITULATES PHYLOGENY”

[‘Ontogeny’ means “the development of an individual organism”; ‘phylogeny’ means “the

evolutionary history of a certain kind of organism”.]

This idea, which the 19th century

semi-materialist naturalist Ernst Haeckel called his “biogenetic law”, is basically that the

embryological development of an individual creature is a recapitulation of the stages of

the historical evolution of that species. Thus early embryos of humans and other mammals have

gills and a fish-like tail recalling their ancient fish ancestry. Modern biological science,

however, considers the idea that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny to be sort of a very crude

and very limited partial truth.

“There is in fact a peculiar correspondence between the gradual development of organic germs into mature organisms and the succession of plants and animals following each other in the history of the earth.” —Engels, Anti-Dühring (1878), MECW 25:69.

“The same phenomenon is illustrated by the gill arches that still dominate the ontogeny of land-living vertebrates. It is obvious in all these cases that development is controlled by such a large number of interacting genes that the selection pressure to eliminate vestigial structures is less effective than the selection to maintain the efficiency of well established developmental pathways.” —Ernst Mayr, Toward a New Philosophy of Biology: Observations of an Evolutionist (1988), p. 435.

ONTOLOGICAL ARGUMENT [For the Existence of God]

The (fallacious) argument that God must exist as a consequence of the very definition

of the word ‘God’. Spelled out more completely:

God is, by definition, a totally perfect

entity. An entity would be less than perfect if it did not exist. Therefore, God exists.

This silly argument was originated by “Saint”

Anselm (1033-1109), Bishop of Canterbury and medieval Scholastic

philosopher. Even most other theologians (including Thomas

Aquinas) have recognized that this argument cannot be accepted as sound.

In Anselm’s own day it was pointed out that

just because we can form the concept of a “perfect island” it does not follow that a perfect

island really exists. No definition of anything can prove that that thing actually

exists in the real world. You can define a “round-square” as a Euclidean two-dimensional

geometrical figure which is both round (a circle) and at the same time a square,

but no such thing can really exist. Moreover, the notion that any real thing can be “perfect”

in every way is totally incoherent. Even if it makes any sense to say that something is

“perfectly smooth” or “perfectly rough”, it cannot possibly be both at the same time. In other

words, some forms of “perfection” preclude other forms. And there are many other conceptual

and logical problems with each of the numerous versions of the ontological argument.

ONTOLOGY

1. The branch of metaphysics

(in the non-Marxist sense) which discusses the nature of existence or reality in the abstract, what sort

of entities actually may be said to exist, and so forth.

2. [More narrowly, but still usually within the milieu

of bourgeois philosophy:] The set of entities or substances which are said to exist. The

dualist’s “ontology”, for example, includes not only matter

but also—independent of matter—mind and possibly “spiritual substances” (such as “souls”

or “gods”). The materialist’s “ontology” includes only matter and energy (or “matter in motion”); and mental

phenomena are viewed as functional characterizations of certain highly complex material entities (e.g., brains)

as they change and internally reorganize.

Thus, in both of these senses, the term ontology is

an absurdly esoteric and pretentious way of talking about the central question of philosophy, namely, what

sort of things actually exist, and which is fundamental—mind or matter.

[From an obituary for the Jamaican-raised American philosopher, Charles W. Mills (1951-2021):] “Rigorous, and persuasive, his work was also free of the jargon and obscurantism that bedevils so much of modern philosophy. He could also be disarmingly funny, often poking fun at himself or his profession. ‘If you are a member of the American Philosophical Association and you don’t use the word ontology in a talk, there’s someone from the A.P.A. sitting in the back of the room and your membership card will be yanked,’ he quipped.” —Clay Risen, “Charles W. Mills, 70, Philosopher of Race and Liberalism, Is Dead”, New York Times, National Edition, Sept. 29, 2021.

“OPEN AND ABOVE-BOARD”

See also:

DOUBLE-DEALING

“The case of Kao Kang and Jao Shu-shih serves as an important lesson for our Party, and all the members should take warning and make sure that similar cases will not recur in the Party. Kao Kang and Jao Shu-shih schemed and conspired, operated clandestinely in the Party and surreptitiously sowed dissention among comrades, but in public they put up a front to camouflage their activities. These were precisely the kind of vile activities the landlord class and the bourgeoisie usually resorted to in the past. In the Manifesto of the Communist Party Marx and Engels say, ‘The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims.’ As Communists, let alone as senior Party cadres, we must all be open and above-board politically, always ready to express our political views openly and take a stand, for or against, on each and every important political issue. We must never follow the example of Kao Kang and Jao Shu-shih and resort to scheming.” —Mao, “Speeches at the National Conference of the Communist Party of China: Opening Speech” (March 21, 1955), SW 5:156.

OPEN DOOR POLICY

1. A policy (or goal) of early United States

imperialism toward China, which sought to keep U.S. trade and general economic access to China

and other areas open on an equal basis with other imperialist countries. In the late 19th

century the major imperialist powers started grabbing more and more parts of the undeveloped

world—especially in Africa—to be their own private colonies which they alone were allowed to

exploit (or at least in which they had many special privileges). The United States, as a

later-developing imperialist country, was very concerned that it was being frozen out of more

and more regions. In 1899 the U.S. Secretary of State John Hay sent a diplomatic note, referred

to as the “Open Door Note”, to the European powers proposing that China be kept open to trade

with all other countries on an equal basis. In other words, all of them (including the U.S.)

would be allowed to exploit China on equal terms. Thus no imperialist power should have any new

special areas of influence or control in China which the other imperialist powers did not share,

nor any unilateral agreements with or favors forced out of the Chinese government for that

power’s exclusive benefit. The stated areas of concern were the development special tariff

arrangements, the elimination or reduction of harbor dues and railroad charges for one power

alone, and similar things. But the overall scope of the Open Door Policy went far beyond

this.

As it turned out, U.S. imperialism at that time

was largely unable to achieve their “Open Door” goal. There were numerous secret deals being

forced on China by separate imperialist powers; existing forced arrangements, let alone existing

territorial seizures (such as by Britain in Hong Kong and by Portugal in Macao) were not ended;

and worst of all Japan totally flouted the “Open Door” principle beginning with its seizure of

Manchuria in 1931, and its later massive invasion of China from 1937 until the end of World

War II.

In history classes in the U.S. the “Open Door”

policy is portrayed as being “opposed” to imperialism—because it was opposed to individual

imperialist powers carving up China into colonies, and the like. Actually, this policy was more

like an early indication of a new form of imperialism that the United States would later

lead in establishing in the world following World War II. What the U.S. was already pushing,

even in the 1890s was a new neocolonialist

World Imperialist System.

2. Similar policies or goals by the U.S. or

other imperialist powers at various times and places, when they thought they were being blocked

by their imperialist competitors in exploiting some country or region of the world.

3. Occasionally the term “open door” is also used

to refer to the policy adopted by the Chinese capitalist-roaders led by Deng

Xiaoping in the 1980s to “open up” China to foreign investment.

OPEN-SOURCE SOFTWARE

Computer software which is written mostly by unpaid volunteer labor

and which is made freely available for anyone to use, often with only the condition that any

improvements made to it must then also be made available free for others to use. Writing and using

open-source software appeals to many people, whether or not they understand from a political

perspective that this more or less arises from natural human creative and communist impulses. (Many

workers, and not just software writers—and even though they must of course have some means of surviving

economically—are often really more interested in collectively producing useful things for people than

they are in getting rich in the process.)

Open-source software has been impressively successful

even in the present capitalist world. However, capitalist corporations have found a way to make

profits even from free software by selling support services for it, and the like.

“To the average capitalist ‘open source’ software may seem like a pretty odd

idea. Like most products, conventional computer software—from video games to operating systems—is

developed in secret, away from the prying eyes of competitors, and then sold to customers as a

finished product. Open-source software, which has roots in the collaborative atmosphere of

computing’s earliest days, takes the opposite approach. Code is public, and anyone is free to

take it, modify it, share it, suggest improvements or add new features.

“It has been a striking success. Open-source

software runs more than half the world’s websites and, in the form of Android, more than 80% of

its smartphones. Some governments, including Germany’s and Brazil’s, prefer their officials to

use open-source software, in part because it reduces their dependence on foreign companies. The

security-conscious appreciate the ability to inspect, in detail, the goods they are using. It is

perfectly compatible with making money. In July IBM spent $34 billion to buy Red Hat, an American

maker of a free open-source operating system [Linux], which earns its crust by charging for

ancillary services like customer support and training.”

—“Open Season: The rise of open-source

computing is good for competition—and may offer a way to ease the tech war”, leader (editorial)

in The Economist, Oct. 5, 2019, p.13.

OPERATION GREEN HUNT

A large-scale anti-Maoist military campaign launched in the fall of 2009 by the Indian central

government together with the paramilitary forces of several states in India, and expected to

last for at least several years. The initial military operations began around Nov. 1, 2009, and

much larger operations are expected in the first months of 2010. A major focus of OGH is in

the Adivasi (tribal) areas in east-central India, where the

Communist Party of India (Maoist) has made much progress in organizing and leading the people

in mass struggles in resistance to the theft and despoilation of their land by giant mining

companies and other Indian and transnational corporations. In effect, OGH is aimed as much at the

Adivasi masses as it is at their Maoist leadership; it is in reality a war by the Indian government

against its own people.

A large-scale anti-Maoist military campaign launched in the fall of 2009 by the Indian central

government together with the paramilitary forces of several states in India, and expected to

last for at least several years. The initial military operations began around Nov. 1, 2009, and

much larger operations are expected in the first months of 2010. A major focus of OGH is in

the Adivasi (tribal) areas in east-central India, where the

Communist Party of India (Maoist) has made much progress in organizing and leading the people

in mass struggles in resistance to the theft and despoilation of their land by giant mining

companies and other Indian and transnational corporations. In effect, OGH is aimed as much at the

Adivasi masses as it is at their Maoist leadership; it is in reality a war by the Indian government

against its own people.

Many news articles about OGH, background

articles, and statements of opposition to the campaign, can be found at the following websites:

https://www.bannedthought.net/India/MilitaryCampaigns/

— BannedThought.net page on Military Assaults on Revolutionaries and People’s Movements in

India

OPERATION PAPERCLIP

The secret U.S. government program after World War II which brought German Nazi scientists to the

the U.S. to work on military projects for U.S. imperialism in its Cold War against the Soviet Union.

The role of these German scientists during the WWII, mostly quite fervently in support of Nazism,

and which amounted to outright mass murder, was conveniently “overlooked” and forgotten. The most

well-known example of these Nazi scientists was the rocket expert Wernher von Braun, who despite his

Nazi Party membership and his personal involvement in the literal enslavement of workers and the

deaths of at least thousands of them (not to mention the greater number of thousands that his

rockets killed), was transformed into an “American hero” by the U.S. ruling class as part of their

Space Program.

See also:

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT [Jacobsen quote]

“[I]n the aftermath of the German surrender more than sixteen hundred of

Hitler’s technologists would become America’s own....

“Under Operation Paperclip, which began

in May of 1945, the scientists who helped the Third Reich wage war continued their

weapons-related work for the U.S. government, developing rockets, chemical and biological

weapons, aviation and space medicine (for enhancing military pilot and astronaut performance),

and many other armaments at a feverish and paranoid pace that came to define the Cold War.”

—Annie Jacobsen, Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi

Scientists to America (2014), p. ix.

OPERATION SPLINTER FACTOR

A Cold War era intelligence operation of the Office of

Policy Coordination of the U.S. State Department designed to sow unfounded suspicion, disunity

and disruption, within the International Communist Movement and the Soviet Bloc, in particular. It

had some considerable success in this effort, partly because of the excessive suspiciousness of

people by Joseph Stalin.

The OPC, despite its bland name, was a secret

“black ops” agency engaged in nefarious activities of the sort which later characterized the CIA.

Starting around 1949, under the instigation of Allen Dulles, Frank Wisner and their associates,

the OPC secretly led Soviet agents and other Communists in Europe to believe that some Communists

or friends of the Soviet Union, were actually American spies. (Some of them had in fact met Allen

Dulles, though they were by no means working for him.) Among the individuals who were

“snitch-jacketed” in this way was Noel Field, a pacifist

Quaker who was an antifascist and sympathetic to the Soviet Union. Field was then lured to Prague

in Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakia with the offer of a teaching job. He was then secretly

arrested by the authorities there and taken to a prison in Hungary and tortured. Meanwhile Noel

Field’s disappearance alarmed his wife Herta and his brother Hermann, who went to Czechoslovakia

to search for him. They too were arrested and tortured. Finally, a young German friend of the

Field family, Erica Wallach, who had been rescued by them during World War II and sort of adopted

into their family, also went to search for the Fields, and after asking for information from the

political authorities in East Berlin she too was arrested, harshly interrogated, and sent off for

five years to first Berlin’s Schumannstrasse Prison and then to the Vorkuta prison labor complex

in the Soviet Arctic wastelands. It was only after Stalin’s death that these people were freed,

and apologies given to them. Many other people were victimized in similar ways, and the disruption

to the world revolutionary movement was quite serious.

“Operation Splinter Factor succeeded beyond the OPC’s wildest dreams. Stalin became convinced that the Fields were at the center of a wide-ranging operation to infiltrate anti-Soviet elements into leadership positions throughout the Eastern bloc. The Dulles-Wisner plot aggravated the Soviet premier’s already rampant paranoia, resulting in an epic reign of terror that, before it finally ran its course, would destroy the lives of untold numbers of people. Hundreds of thousands throughout Eastern Europe were arrested; many were tortured and executed. In Czechoslovakia, where nearly 170,000 Communist Party members were seized as suspects in the make-believe Field plot, the political crisis grew so severe that the economy nearly collapsed.” —David Talbot, Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government (2015), p. 155. [Talbot is an anti-communist liberal, and it is possible that he is exaggerating things here, at least with regard to the role of the Field family specifically in all this. Nevertheless the story he tells in chapter 7 of this book is hair-raising indeed. —S.H.]

OPINION

“1. A view, judgment, or appraisal formed in the mind of someone about a particular matter; or 2. A

belief stronger than an impression and less strong than positive knowledge.” [Merriam Webster’s

Collegiate Dictionary, 10th Ed. (1993)]

While everyone has a large number of opinions about

lots of different things, there is a strong tendency for people in present-day bourgeois society to

disapprove of anyone having non-standard opinions particularly in certain special areas, such as with

regard to religion or politics. Thus Christians are often offended by the opinion of atheists (or

adherents of other religions) that their Christian views are anti-scientific nonsense. Despite the

often expressed remark that others “have a right to their own opinion”, many people in this society

do not really believe this. Similarly, some individuals who are deeply indoctrinated with bourgeois

points of view, think that revolutionaries have no real right to their opinion that the people should

rise up and overthrow the capitalist system, let alone the right to publicly express that

opinion!

But what about us Marxists? (We are speaking of real

Marxist-Leninist-Maoists, of course, not revisionist phonies!) Do we really believe that those who

disagree with us have a right to their own opinion? Well, certainly for those among the working

class and masses, yes we do! And we also uphold the right of members of the proletariat and of the

masses to publicly express their opinions, even when they disagree with us! Indeed, we really want

to hear those negative opinions and criticisms (along with their progressive and revolutionary opinions),

and to really get to know them. It is a major task of the members of the revolutionary party to gather

the actual ideas and opinions of the masses, and to transmit them to the party leadership. All

their widespread ideas, both progressive and backward.

Party members and supporters themselves will naturally

put forward revolutionary ideas and opinions to the masses and struggle against what we see as backward

or incorrect views that we sometimes hear from them. But we are determined to support the democratic

rights of the working class and masses to have and express their opinions, whatever they might be.

As for the enemy in socialist society, the remaining

capitalists and proven enemies of socialism, they too will have a right to their own opinions, and we

would like to know what they are too! But under the dictatorship of the proletariat, those reactionary

elements will not have the right to broadly spread their reactionary ideas among the masses, as they

always do in present-day capitalist society. —S.H. [June 27, 2025]

“One should not be drawn to new opinions, that is, those that one has discovered. [Instead] one must adhere to the old and generally accepted opinions ... and follow the true and sound doctrine.” —Benito Pereira, theologian of the Collegio Romano, 1564. Quoted in Amir Alexander, Infinitesimal, (NY: Scientific American, 2014), p. 55. [Not only do religious reactionaries want to suppress revolutionary ideas and opinions, they even want to suppress any other new or different opinions even from within their own ranks! —S.H.]

OPINION POLLS

See:

AMERICAN INSTITUTIONS — Public Support For,

CONGRESS (U.S.)

OPIOID ADDICTION CRISIS [U.S.]

See also:

FENTANYL

“America is battling a massive epidemic of heroin and its pharmacological substitutes. By 2008 drug overdoses, mostly from opioids, overtook car crashes as the leading cause of accidental death. In a related development, the number of annual users of heroin jumped from 370,000 in 2007 to 780,000 in 2013.” —“America’s Opioid Problem: Poppy Love”, The Economist, Aug. 1, 2015, p. 72.

“In the last two decades, more than 500,000 Americans have died from overdoses of prescription and illegal opioids.” —New York Times, “15 States Sign On to the Deal for the $4.5 Billion Settlement With Major Opioid Maker”, July 9, 2021.

“Between 1991 and 2012, at the height of the prescription phase of the opioid crisis in the United States, doctors were prescribing enough opioids for every American adult to get their own bottle of pills.” —New York Times, “Opioid v. Opioid”, The Magazine, p. 30, February 16, 2025.

OPIUM — and Religion

See also: OPIUM WARS

entry below. For Marx’s comment about religion being “the opium of the people”, see the entry

RELIGION—As a Palliative

“Jardine Matheson and Co. had become the biggest opium house in Canton, but they did not let matters rest there. Instead they sent ships up the China coast looking for new markets. The clippers, with a broadside of four or five guns port and starboard and a heavy gun amidship, were more formidable than any naval force the Emperor might put against them. They sailed up the Kwangtung and Fukien coasts to Amoy and Foochow, where they would be able to sell opium, often accompanied by Protestant missionaries who acted as interpreters for the captain and crew. The missionaries, obsessed with the printed word of God, would dispense versions of the Bible awkwardly translated into Chinese from one side of the ship while opium was sold from the other side. Christ, however, did not prove to be as irresistible as opium.” —Possibly taken or derived from John Fairbank, Trade and Diplomacy on the Coast: The Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842-1854 (1969).

OPIUM WARS

Two imperialist wars of British imperialism against China during the 19th century which (among

other crimes) forced China to allow British traders to import opium into China and sell it there.

The first Opium War was in 1839-1842 and the second in 1856-1858. British Foreign Secretary

Lord Palmerston sent British troops to compel China to accept the import of opium against its

strenuous objections, and 20,000 Chinese soldiers were killed by the British in the war that

followed. These Opium Wars led to the introduction of the term “gunboat diplomacy” to describe

the forced compliance of “Third World” countries to the demands

of the imperialist powers.

A good short introduction to this sordid

imperialist history is the article “The Opium War”, by C. Clark Kissinger, in the Revolutionary

Worker, #734, (Dec. 5, 1993), page 11, available online at:

https://www.bannedthought.net/USA/RCP/RW/1993/RW734-English.pdf, and an excellent more

extensive history is the book The Opium War, History of China Series, (Peking: FLP, 1976),

149 pages, online at:

https://www.bannedthought.net/China/MaoEra/History/TheOpiumWar-FLP-1976.pdf [PDF format:

6,768 KB]

“The collective white man had acted like a devil in virtually every contact he had with the world’s collective non-white man. The blood forebearers of this same white man raped China at a time when China was trusting and helpless. Those original white ‘Christian traders’ sent into China millions of pounds of opium. By 1839 so many of the Chinese were addicts that China’s desperate government destroyed 20,000 chests of opium. The first Opium War was promptly declared by the white man. Imagine! Declare war upon someone who objects to being narcotized!” —Malcolm X, quoted in C. Clark Kissinger, “The Opium War”, op. cit. [This comment by Malcolm X brings out the racist aspect of this outrageous imperialist crime. —Ed.]

OPPORTUNISM [Marxist-Leninist senses]

1. The political line and activity of an individual,

group of people, or a political party who, though claiming that they are revolutionaries

working to overthrow capitalism, in reality only work for some of the short-term interests

of the proletariat in achieving reforms. In other words, in its most common usage, opportunism

pretty much means the same thing as reformism.

2. A type of revisionism

within MLM parties, whose essence is well summed up by Lenin in the following quotations:

“The idea of class collaboration is opportunism’s main feature....

“Opportunism means sacrificing the

fundamental interests of the masses to the temporary interests of an insignificant minority of

the workers or, in other words, an alliance between a section of the workers and the bourgeoisie,

directed against the mass of the proletariat.” —V. I. Lenin, “The Collapse of the Second

International”, section VII, (May-June 1915), LCW 15.

“The opportunist does not betray his party, he does not act as a traitor, he does not desert it. He continues to serve it sincerely and zealously. But his typical and characteristic trait is that he yields to the mood of the moment, he is unable to resist what is fashionable, he is politically short-sighted and spineless. Opportunism means sacrificing the permanent and essential interests of the party to the momentary, transient and minor interests.” —V. I. Lenin, “The Russian Radical is Wise After the Event” (Oct. 18, 1906), LCW 11:239.

“Once again [Alexander] Parvus’ apt observation that it is difficult to catch an opportunist with a formula [or mutually agreed-upon political statement] has been proved correct. An opportunist will readily put his name to any formula and as readily abandon it, because opportunism means precisely a lack of definite and firm principles.” —V. I. Lenin, What Is To Be Done? (Feb. 1902), Appendix, LCW 5:525.

“Opportunism does not extend recognition of the class struggle to the cardinal point, to the period of transition from capitalism to communism, of the overthrow and the complete abolition of the bourgeoisie.” —V. I. Lenin, “The State and Revolution” (Aug.-Sept. 1917), chapter II, section 3; LCW 25:412.